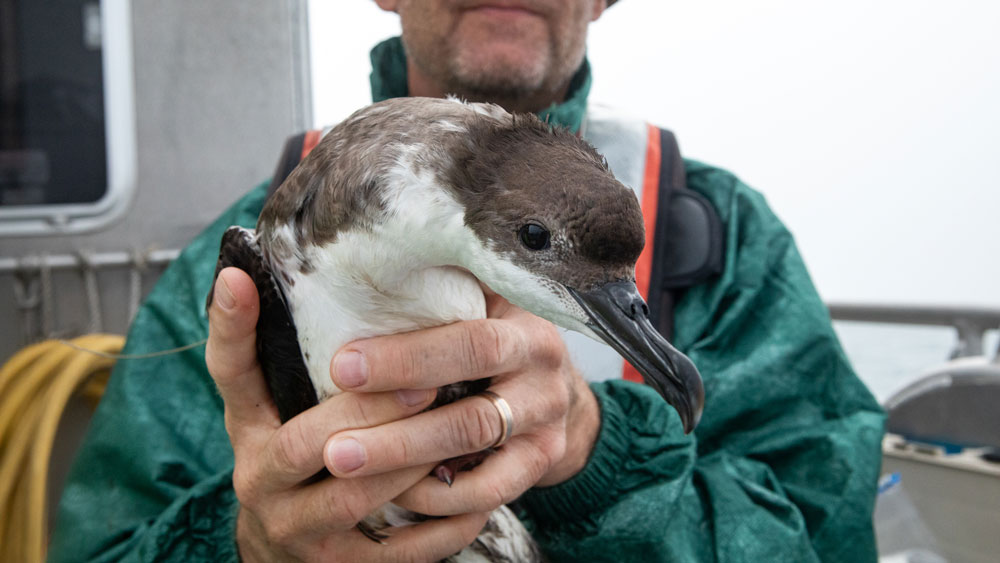

Since 2013, researchers at NOAA's Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary have been using satellite technology to study the movements, life cycle, and feeding and foraging habits of great shearwater seabirds in the Gulf of Maine ecosystem. After attaching transmitters to the backs of the birds, the scientists then follow their movements from the signals sent out by the tags.

In 2021, 15 birds will be fitted with the transmitters, which are placed on their backs and attached with degradable thread. Small and lightweight, the tags do not interfere with flight, and are equipped with mini solar panels that provide the technology with long life. In recent years, several tags have survived well into the winter, giving the science team the bonus of being able to follow the birds’ migratory paths into the South Atlantic.

Why follow the birds’ movements? Sanctuary scientists believe that seabirds -- especially great shearwaters, one of the most common seabirds in the sanctuary -- are excellent indicators of ecosystem health, and may provide insights into impacts of climate change. Alterations in water temperature, currents, or other factors can seriously impact the seabirds’ food supply. These birds prey primarily on sand lance, a small pencil-like schooling fish, which is an important food for many large predators in the Gulf of Maine, including whales, dolphins, bluefin tuna, and other important commercial and recreational species.

Five more names are being held for great shearwaters that will be tagged in September.

Arliner: 7/14/21; named for Roger Arliner Young, the first African American woman to receive a PhD in Zoology and be professionally published in her field. She worked summers at the Marine Biological Laboratory on Cape Cod with Ernest Everett Just where she studied hydration and dehydration of living cells and fertilization in marine invertebrates. The RAY Marine Conservation Diversity Fellowships were established in her honor.

Ashanti: 7/13/21; named for Ashanti Johnson, one of first Black female chemical oceanographers, and first African American to earn a doctoral degree in oceanography from Texas A&M University. She is active in diversity-focused initiatives in academia and was awarded the 2010 Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics, and Engineering for her work in STEM education.

Bessie: 7/14/21; named for Bessie Coleman, the first African American woman and Native American woman to hold a pilot’s license. This famous trick pilot was killed at age 34 in an unfortunate plane accident. A Bessie Coleman Aviators Club was founded in 1977 by African American women pilots and the U.S. Postal Service issued the Bessie Coleman stamp in 1995.

Birdy McBirdface: 7/13/21; this name is the somewhat inevitable consequence of an earlier contest (2016), sponsored by the British government, to name a new polar research ship. The public selected Boaty McBoatface, which although meeting the naming rules, was not used for the large vessel, but assigned to an autonomous underwater vehicle (marine robot). Several entries of Birdy McBirdface were received, accepted, and selected by the team.

Britney Shears: 7/13/21; this name plays off the species name and the name of a famous pop singer.

E.E.Just: 7/13/21; named for Ernest Everett Just, a brilliant student and pioneering African American biologist, who was the first recipient of the NAACP’s Springarn Medal for his scientific achievements. One of the first African Americans to earn a PhD from the University of Chicago, Just worked with Frank R. Lillie, director of the Marine Biological Laboratory, who served as his doctoral advisor. Later in his career, Just mentored Roger Arliner Young (see above). He was a founding member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity (Alpha Chapter) at Howard University in 1911.

Jemison: 7/13/21; named for the first Black woman to travel into space. Mae Carol Jemison is an engineer and physician. She served as a mission specialist aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour in 1992, during which she orbited the Earth for nearly eight days. Since leaving NASA she has formed a non-profit educational foundation.

Shuri: 7/14/21; named for a character in the Black Panther movie. Shuri is the Princess of Wakanda and the daughter of T’Chaka and Ramonda. She is the sister of T’Challa and a scientist/inventor who created much of the technology used in her nation.

Tuskegee: 7/13/21; named for the World War II Tuskegee Airmen—the first African American fighter pilots for the U.S. Army Air Corps. Some of these pilots trained over the Great Lakes where six airmen and their aircraft were lost in the lakes. Recently, archaeologists have been working to find these aircraft to honor the pilots and protect the sites. One of the lost Tuskegee Airmen, Lt. Frank Moody, was killed when his Bell P-39Q Airacobra crashed in 1944. The aircraft was discovered in 30 feet of water in Lake Huron and documented by Michigan state maritime archaeologist Wayne Lusardi and partners from Thunder Bay National Marine Sanctuary and the NOAA Office of Ocean Exploration and Research.

Volgenau8: 7/13/21; named for the Volgenau Foundation, an organization that has financially supported the project for the past decade. During the 10-year study to date, no names were assigned in year one and no birds were tagged in 2020 due to the pandemic, hence the “8” in this year’s bird name.

Sanctuary scientists want to learn more about how seabirds react to changes in their primary food source and what factors cause changes in forage fish abundance. Signals from the tags have allowed scientists to plot bird movements. They can then relate the movements to oceanographic features such as water temperature, bathymetry, chlorophyll concentration, ocean fronts and other factors that might result in increased productivity or that concentrate prey. This year, two tagging missions will attempt to tag sets of mature and immature birds to study differences in feeding patterns and migration routes.

Summary reports of the birds’ travels and cumulative maps of each bird’s tracks will be updated monthly on our follow the birds page. The maps are to be used for educational purposes only. For more timely notices, check our Twitter (@NOAASBNMS) and Facebook and the project's associated twitter account @TrackSeabirds.

For Educators: The sanctuary offers two maps for tracking shearwater movements. One map is for the Gulf of Maine and the second is of the Atlantic Ocean (North and South Basins). The coated surface on the paper allows for the placement and removal of sticky dots for repeated use. The sanctuary education team has prepared a generic tracking activity and other background materials. Email stellwagen@noaa.gov for more information.

The Team: Dr. David Wiley, research ecologist for the sanctuary, leads the shearwater tagging project. Additional sanctuary staff include Michael Thompson, sanctuary geographer and GIS specialist, and Dr. Tammy Silva, postdoctoral researcher, along with Kevin Powers, a volunteer with the Stellwagen Sanctuary Seabird Stewards program and seabird expert. The research team includes Linda Welch, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service seabird specialists at the Maine Coastal Islands National Wildlife Refuge, Dr. Les Kaufman, Boston University, Dr. Kent Hatch, Long Island University, Dr. Anna Robuck, University of Rhode Island, and Dr. Robert Ronconi Environment and Climate Change Canada. Funds for the project have been provided by the Volgenau Foundation, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, the Davis Foundation, and the Mudge Foundation.

The great shearwater (Ardenna gravis) is a gull-like seabird that is dark above and white below, with a dark cap on its head and dark coloring on the trailing part of its tail. It has a white band around its neck, a black bill, and a white rump patch. It is one of the larger birds in the seabird family Procellariidae. Three other shearwater species also visit the sanctuary – the similarly sized all-dark sooty shearwater, the larger Cory’s shearwater with a light brown head without the white neck band, and a smaller Manx shearwater whose dark coloring extends from its head directly to the back.

In the sanctuary, great shearwaters feed primarily on small schooling fish, particularly sand lance. The birds often come together in large groups that include various gull species and other shearwaters, and have been observed near feeding humpback whales, targeting fish that evaded the larger predators. They also follow fishing boats, eating discarded offal and scraps.

Great shearwaters will glide over the wave tops with stiff outstretched wings. To catch fish, they undertake short plunges from the air, dive from the surface and swim underwater, or pick items from the surface. Once sitting on the ocean’s surface, the birds need to take a running start to get airborne. They breed during our winter season on the Tristan da Cunha Islands (Tristan da Cunha, Nightingale Island, Inaccessible Island, and Gough Island) in the southern part of the South Atlantic Ocean in large dense colonies where the female lays one white egg on open grass or in a small burrow. Northern feeding grounds range from Florida to the Labrador Sea (south of Greenland).

Their migratory route is a "great circle" or, more figuratively, a “great eight.” From their breeding grounds on the Tristan da Cunha Islands (considered the most remote island on the planet) or the Patagonian Shelf off South America for the non-breeders, the shearwaters fly north to their feeding grounds, arriving in the sanctuary and Gulf of Maine as early as April. At the end of the summer, many birds fly to the Eastern Atlantic, to areas off the Azores and west coast of North Africa. The next stage takes the birds westward to waters off Brazil and more southern feeding areas off Uruguay and Argentina. Breeding birds now shift east to the Tristan da Cunha Islands while non-breeders remain close to South America.